“We've arranged a global civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.”

- Carl SaganNow that Neil deGrasse Tyson has schooled rapper B.o.B. on how wrong it is to believe the earth is flat can we finally have an honest discussion about how we know it's moving? Unlike some of the evidence for sphericity the evidence for Earth's motion can't easily be captured in a cartoon or a photo. Just how certain are you of this basic fact about our world, and - more importantly - how do you know?

It seems like almost everyone nowadays has a strong opinion and a plethora of supporting "facts" for or against evolution, climate change, vaccines, genetically modified foods, and a host of other complex scientific questions. Heated debates occur regularly in Congress and around the water cooler at work or the dinner table at Thanksgiving. Nuance is avoided at all costs. Certainty reigns on all sides. Single data points or lines of evidence are offered up as "proof" - the "smoking gun" to silence our critics once and for all. We are confident that we are right and our critics are wrong. We are all graduates from the "University of Google." We research the issues ourselves. How can we possibly be wrong? In a collection of essays written by the British philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell in the early twentieth century, he noted that "the fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt" (Mortals and Others). In our Information Age this problem only seems to have gotten worse.

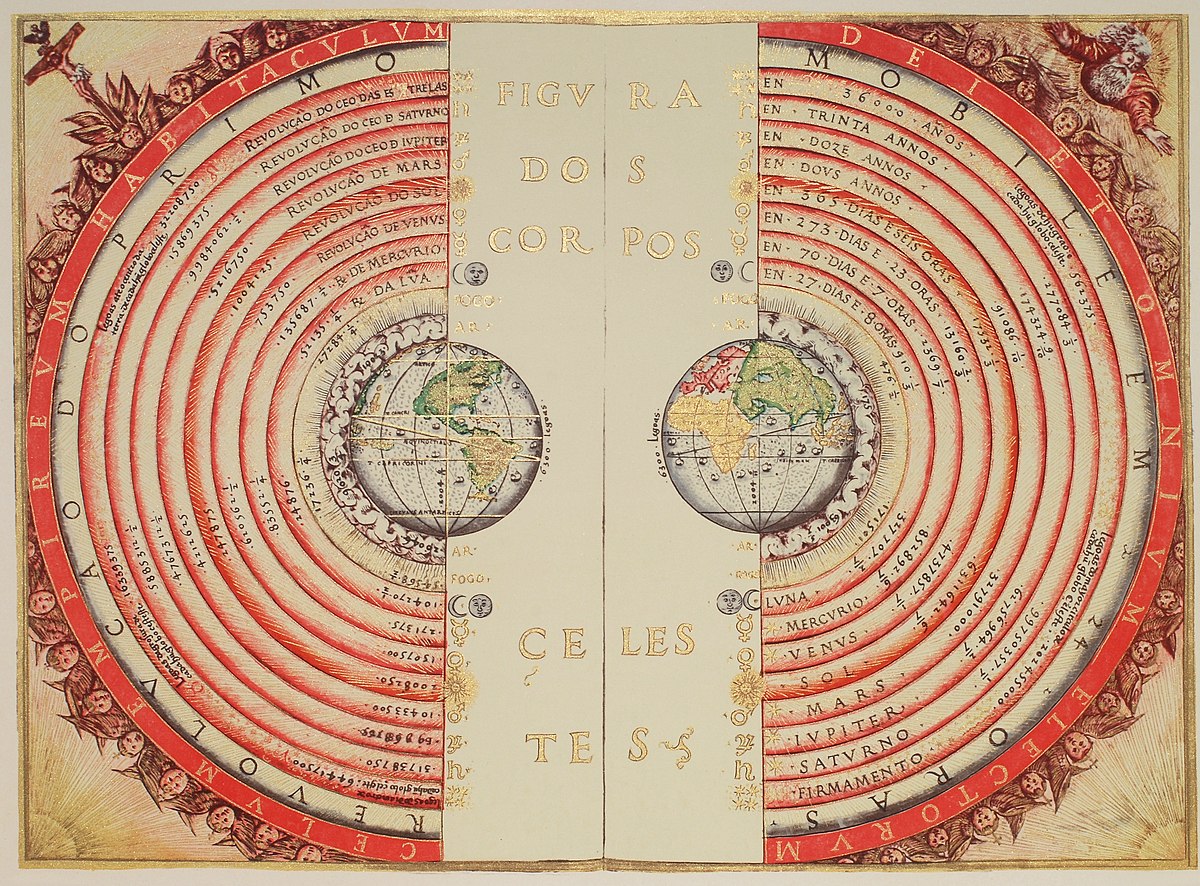

This politically charged public discourse on certain scientific issues stands in stark contrast to a general consensus on other similarly complex empirical questions. For example, according to a recent survey by the National Science Foundation, three quarters of Americans believe that the Earth revolves around the Sun. How hard would it be to convince those who are ignorant of this basic fact about our world? We experience direct evidence of geocentrism every day. It is embedded in our language (sunrise and sunset) and our tools (maps, globes, and star charts). And few of us can cite, much less have observed, any evidence whatsoever for heliocentrism. Science tell us that the Earth is moving at about 100,000 kilometers per hour around the Sun and spins on its axis at about 1,670 kilometers per hour at the equator. So we're not only moving, we're moving very fast!

Why do most of us accept this counterintuitive fact about our world? Why don't we have politically charged debates about it? Why are geocentrists (and Flat Earthers like B.o.B) viewed as fringe and nutty cranks while evolution, climate change, and vaccine "skeptics" are embraced by some celebrities, powerful politicians, taxi drivers, and janitors? How does a man named Oz become "one of American's most trusted docs" (according to NBC) while promoting untested weight loss supplements such as raspberry ketones and green coffee beans as a "miracle in a bottle" and a "magic weight-loss cure"? How did the "Food Babe" become a New York Times best-selling author and one of "the 30 most influential people on the internet" (according to Time Magazine) by promoting nutritional pseudoscience on her blog? Why does a major party presidential candidate and former First Lady of the United States believe (or pander to people who believe) that the government is withholding information from us about UFOs?

We have what neurologist Robert Burton has called a "certainty bias" - we "seek escape from ambiguity and indecision." We suppress our doubts. And we are all too willing to embrace strict ideologies and reject ambiguity and critical thinking when our most cherished beliefs are challenged. At the same time, many of us claim to love science - almost 20 million of us are fans of a popular Facebook page called "I fucking love science." But our "scienceyness" seldom leads to any serious questioning or inquiry, and we cling to "facts" that reinforce our preconceived ideas about the world without doing any actual investigation or critical thinking about them.

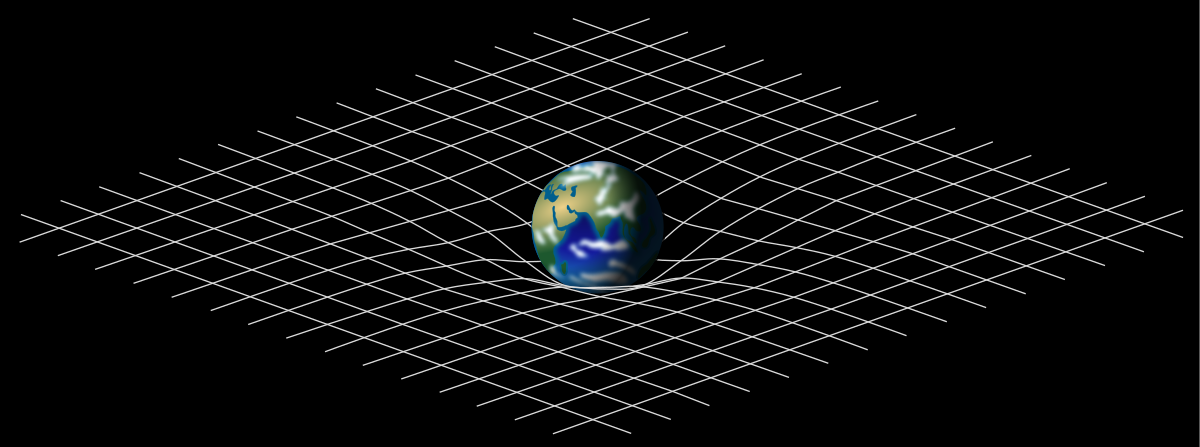

Of course, we can't all be scientists or personally investigate everything ourselves even if we were. We rely on trusted experts as well as our own education, experiences, and intuitions. But I want to challenge you to ignore the former and embrace the latter for just a moment. Let's apply some skepticism to heliocentrism.

|

| Earthrise by NASA / Bill Anders, Public Domain. |